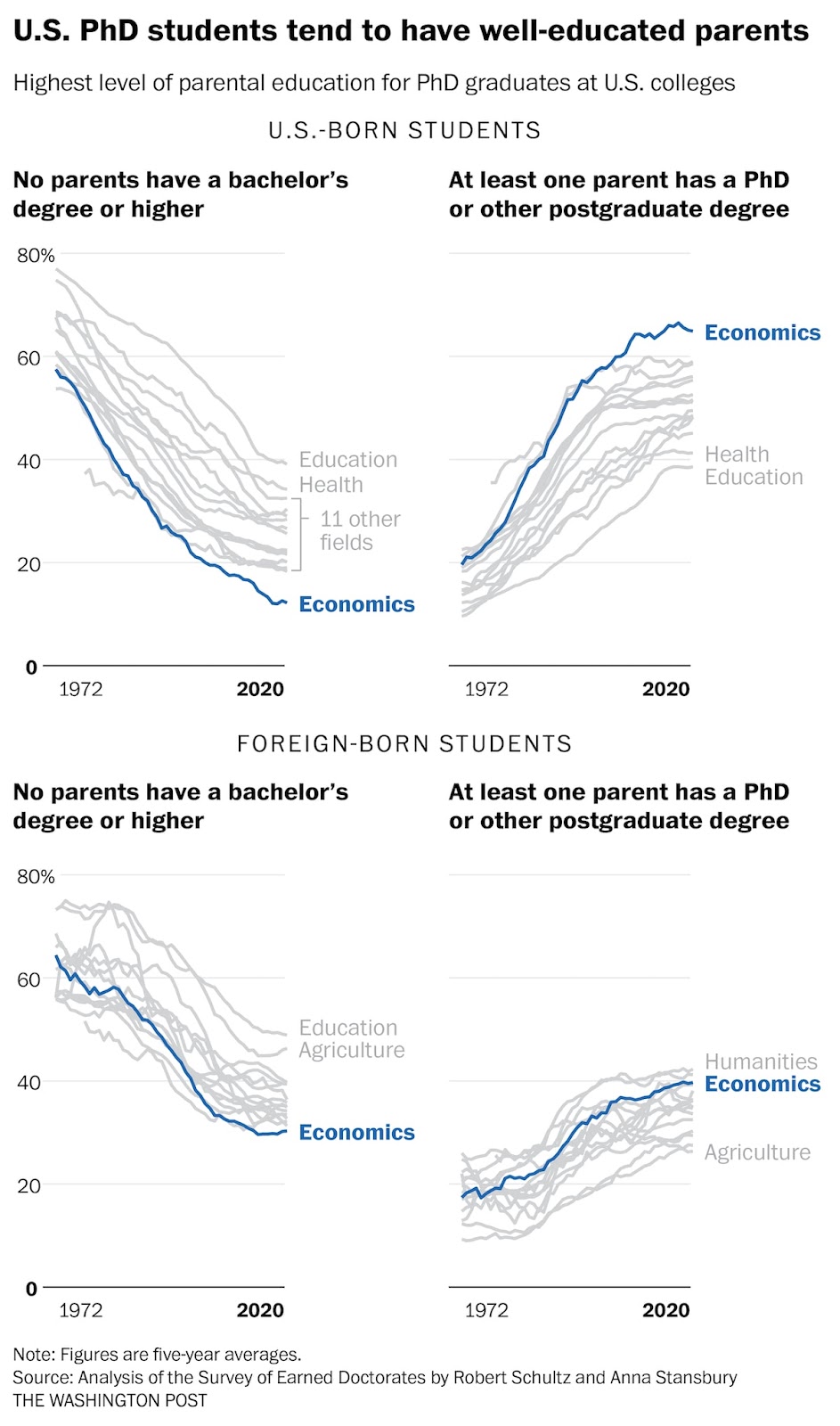

A problem the humanities—and universities in general—haven’t solved: They are playgrounds of the aristocracy that paid a historically temporary visit to populism, which was mistakenly construed as permanent residency.

More accurate: the university has long been both playground of the aristocracy (or haute bourgeois) and means for the upwardly mobile to enter the civil service. In Germany the Humboldts represent the former, Fichte the latter. The late-20th Century inflation of fees is novel...

"Who believes in this? –aside from a few big children in university chairs or editorial offices." Max Weber.

The US isn't Germany. As always: from Brooklyn College students moving to Manhattan, to Harvard grads gentrifying Brooklyn.

There's no way in hell I should be able to do this. But history is bunk.

1960

Whatever Greenwich Village may once have been or may now be supposed to have been, anyone who has recently strayed down MacDougal Street on a Saturday night knows that now it is a playground. What Coney Island was once to the honest workingman, Greenwich Village is now to the unmarried or ex-married young professional. The Village streets, pads, coffee houses, and bars are jammed with people who look a million times more sensitive, artistic, and "interesting" than William Faulkner or Igor Stravinsky, but who live by teaching economics, analyzing public opinion, writing advertising copy, practicing psychoanalysis, or "doing research" for political candidates. They are not intellectuals, but occasionally dream that they will be.

And again.

Perhaps the most exciting component of the curriculum was the series of guest lecturers the institute brought to campus. “One hundred and sixty of America’s leading intellectuals,” according to Baltzell, spoke to the Bell students that year. They included the poets W. H. Auden and Delmore Schwartz, the Princeton literary critic R. P. Blackmur, the architectural historian Lewis Mumford, the composer Virgil Thomson. It was a thrilling intellectual carnival.

...What’s more, the graduates were no longer content to let the machinery of business determine the course of their lives. One man told Baltzell that before the program he had been “like a straw floating with the current down the stream” and added: “The stream was the Bell Telephone Company. I don’t think I will ever be that straw again.”

...But Bell gradually withdrew its support after yet another positive assessment found that while executives came out of the program more confident and more intellectually engaged, they were also less interested in putting the company’s bottom line ahead of their commitments to their families and communities. By 1960, the Institute of Humanistic Studies for Executives was finished.

At the English department I chair, our major has grown by more than 40 percent in the last two years. We are being driven to the edge of extinction anyway....In their interviews with Heller, English faculty and administrators discuss an array of real issues with an alarming lack of coherence. They try to place blame both for what is happening at their own institutions and for what they consider broader national concerns: Middlemarch is too long for the TikTok generation; K-12 education is the problem; humanists haven’t made a strong enough case for how our areas of study prepare debt-ridden students for jobs; funding has dried up; a fusty curriculum drives students away; television exists.

Much more to the point are Heller’s interviews with students, who explain the fundamental problem quite clearly: universities do not value the humanities. This disregard is demonstrated in most universities’ built environments, real estate investments, hiring practices, staffing ratios, and unwillingness to direct resources toward the humanities even in appropriate balance with the often substantial revenue they bring in. I heard in these young people’s comments a real awareness of the funding priorities of the colleges they attend.

Students are quick to associate those priorities with their job prospects: when it comes to deciding on a major, they sense that their own personal, intellectual, and creative interests don’t really matter at all. As Ben Schmidt, a data analyst and former history professor, put it in a 2018 article on the declining number of humanities majors, “In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, students seem to have shifted their view of what they should be studying—in a largely misguided effort to enhance their chances on the job market.” What faculty and administrators have mistaken for a problem (declining enrollments) with an identifiable cause (take your pick), students correctly see as a story being spun by the universities themselves: this area of study lacks value, is in some sense wrong. That story has become powerful enough to shape their world, restricting the number of paths presented to them as real options.

And I should have added this,

"The sociology of modern knowledge production empowers the scholar over the humanist, and the collective/communal enterprise of scholarship over the inspiration of the individual thinker."

You have that precisely backwards. The humanist is embedded in culture by calling, the mathematician only by default, while embedded by choice in a private world of universals. What would you call the communal enterprise of neoclassical formal economics? Would you call it worldly or unworldly? Formal philosophy is formal economics with no need to ignore evidence.

---

June 16th, he rt's a link to a statement by the UK Royal Historical Society. I suppose the monarchist trappings could be taken as confirmation of something.

None of these problems can be explained by a decline in student numbers or interest in History, which remain strong. Instead we must look to political decisions to explain this troubling situation. UK universities now operate in a market economy. Institutions are placed in direct competition, with income generation via intake the principal measure of success. The lifting of the student cap in 2015 has established an environment of ‘feast and famine’ across the sector.

Cuts and closures are the starkest manifestation of this environment. But marketisation also brings turbulence and uncertainty to historians in ‘winning’ institutions, required at short notice to deal with sharp, and unpredictable, spikes in student numbers. Across the sector, uncertainty is exhausting, all-consuming, and impedes long-term thinking, planning and the delivery of high-quality teaching.

In the coming months, the Royal Historical Society is undertaking a project to assess the full extent of the losses, risks and concerns that now characterise History in UK Higher Education. We also seek to better understand the personal, institutional and disciplinary impact of change on academic staff, researchers, students and community partners. As is clear, the aftershocks of upheaval are long-lasting and have negative effects on the life of a department well after a programme of change has officially ended.