Indiana is often associated in the popular mind or the minds of magazine editors with the “Downtown” Manhattan of the 1980s, and while this is not wrong—he was living as he does still, some of the time, in the East Village, was present at the Mudd Club, and so on—it is not enough. The vision of his novels, especially his true crime trilogy (Resentment, Three Month Fever, Depraved Indifference) spans the whole of America, and his literary sensibility is rooted in Europe.

Most of the writers, artists, and filmmakers Indiana scrutinizes in these pages are geniuses, and his criticism meets them at their level. From the fictions of Paul Scheerbart to the paintings of the young artist Sam McKinniss,...

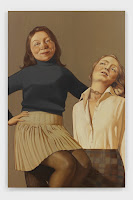

McKinniss’s work arouses thoughts about the Leibnizian fuzziness between fiction and documentary reality, about concealment and revelation, about forms of masquerade, the mutability of memory. His paintings evoke a waking dream where figures of fiction, on furlough from their narratives, have real metaphorical force. Celebrities are fictional, whatever else they are; McKinniss’s pictures of them are layered in artifice, approximations of “perfect moments” in the careers of certain images.

Henri Fantin-Latour (1836–1904), whose flower paintings McKinniss frequently copies, has been called “a traditional painter with avant-garde sympathies,” which could apply to contemporary artists like Dike Blair, Maureen Gallace, Billy Sullivan, and McKinniss, who are realist painters of no discernible school, very different in style, innovators in subject matter and formal design. Alex Katz might fit in here, too. However traditional their techniques, their works are recognizably of our time, informed by the convulsive history of modernism and the wider movement of current events. Even McKinniss’s atmospheric copies of Fantin-Latour have a Pierre Menard kind of postmodernity; we see them through the filter of the past hundred years. (I like the knife on the table that features in Still Life with Primroses, Pears and Pomegranates (after Fantin-Latour), 2018—how criminal!)

McKinniss What Fantin-Latour represents for McKinniss is something close to perfection in paint, the apogee of particular skills and sensitivities that McKinniss also has in abundance. I could be mistaken, but I think McKinniss’s embrace of Fantin-Latour is also his way of telling us he isn’t running for flavor of the month. Both artists are intoxicated by music.

McKinness in the New Yorker, by Jia Tolentino, another young sophisticate who isn't.

Last year, the twenty-year-old New Zealand singer-songwriter Lorde contacted the Brooklyn-based painter Sam McKinniss through mutual friends. She came to visit his studio in Bushwick, and then went to see his exhibition “Egyptian Violet,” which featured, among other works, a life-size oil painting, rendered with Symbolist intensity and high-classical technique, of Prince on a motorcycle. Soon after, she asked McKinniss if he would paint a portrait of her for the cover of her forthcoming album, “Melodrama.”

|

| Currin |

|

| Weyant |

|

| Currin |

A few years ago at Christie's a young thing in the sales department saw me looking at a Gauguin monotype, one image repeated on a page, saying not too pertly, "It's a nice Warhol". I looked at her, surprised. She smiled. We both smiled. Her bosses may have told her what to to say; it may have been her idea. She may have had an intuitive understanding of what it meant to find the human behind the mechanical as opposed to the mechanical behind the human. Or maybe she was being paid to respond equally to both. At the moment I gave her the benefit of the doubt; that's why the young and attractive are out front. I wished I'd had the money for dinner if not the Gauguin. I would have asked. But at this point Indiana and others who also should know better are just scraping the barrel, or trying to get laid.

I've said a few times that over the last 25 years I've had more interesting conversations with art dealers than artists, and even more so with gallerists and employees of auction houses who dealt with a broader range of art: 19th century to contemporary, or even older. If I didn't love the good shit I wouldn't be talking about the bad. And what annoys me almost as much as the ignorance that now rules the "artworld" is the "leftist intellectuals" and academics who refer to art—and film—as if it didn't mark them as absolutely bourgeois, and conservative.

Of course I'm a conservative. All leftists are conservatives. Anarchists are liberal idealists.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comment moderation is enabled.