John Ganz got into a twitter feud with a wise-ass, who turned out to be an asshole, but it started when the asshole made a point that was obvious to Panofsky 90 years ago, though the asshole overstated his case. It wasn't obvious to Ganz so I paid my 5 dollars and subscribed again, just so I could use the quotes I have for years. I riffed a bit on Richter and the art world, told stories and name-dropped. After that I cancelled my account. I don't think Ganz knows it was me. He liked the comment. Or maybe deleting it might have been difficult. Or maybe he'll still do it. If Shadi Hamid can like and delete, why not Ganz?

Film art is the only art the development of which men now living have witnessed from the very beginnings; and this development is all the more interesting as it took place under conditions contrary to precedent. It was not an artistic urge that gave rise to the discovery and gradual perfection of a new technique; it was a technical invention that gave rise to the discovery and gradual perfection of a new art.

From this we understand two fundamental facts. First, that the primordial basis of the enjoyment of moving pictures was not an objective interest in a specific subject matter, much less an aesthetic interest in the formal presentation of subject matter, but the sheer delight in the fact that things seemed to move, no matter what things they were. Second, that films—first exhibited in “kinetoscopes,” namely, cinematographic peep shows, but projectable to a screen since as early as 1894—are, originally, a product of genuine folk art (whereas, as a rule, folk art derives from what is known as “higher art”). At the very beginning of things we find the simple recording of movements: galloping horses, railroad trains, fire engines, sporting events, street scenes. And when it had come to the making of narrative films these were produced by photographers who were anything but “producers” or “directors,” performed by people who were anything but actors, and enjoyed by people who would have been much offended had anyone called them “art lovers.”

The casts of these archaic films were usually collected in a “café” where unemployed supers or ordinary citizens possessed of a suitable exterior were wont to assemble at a given hour. An enterprising photographer would walk in, hire four or five convenient characters, and make the picture while carefully instructing them what to do: “Now, you pretend to hit this lady over the head”; and (to the lady): “And you pretend to fall down in a heap.” Productions like these were shown, together with those purely factual recordings of “movement for movement’s sake,” in a few small and dingy cinemas mostly frequented by the “lower classes” and a sprinkling of youngsters in quest of adventure (about 1905, I happen to remember, there was only one obscure and faintly disreputable Kino in the whole city of Berlin, bearing, for some unfathomable reason, the English name of “The Meeting Room”). Small wonder that the “better classes,” when they slowly began to venture into these early picture theaters, did so, not by way of seeking normal and possibly serious entertainment, but with that characteristic sensation of self-conscious condescension with which we may plunge, in gay company, into the folkloristic depths of Coney Island or a European kermis; even a few years ago it was the regulation attitude of the socially or intellectually prominent that one could confess to enjoying such austerely educational films as The Sex Life of the Starfish or films with “beautiful scenery,” but never to a serious liking for narratives.

Today there is no denying that narrative films are not only “art”— not often good art, to be sure, but this applies to other media as well—but also, besides architecture, cartooning, and “commercial design,” the only visual art entirely alive. The “movies” have reestablished that dynamic contact between art production and art consumption which, for reasons too complex to be considered here, is sorely attenuated, if not entirely interrupted, in many other fields of artistic endeavor. Whether we like it or not, it is the movies that mold, more than any other single force, the opinions, the taste, the language, the dress, the behavior, and even the physical appearance of a public comprising more than 60 percent of the population of the earth. If all the serious lyrical poets, composers, painters, and sculptors were forced by law to stop their activities, a rather small fraction of the general public would become aware of the fact and a still smaller fraction would seriously regret it. If the same thing were to happen with the movies the social consequences would be catastrophic.

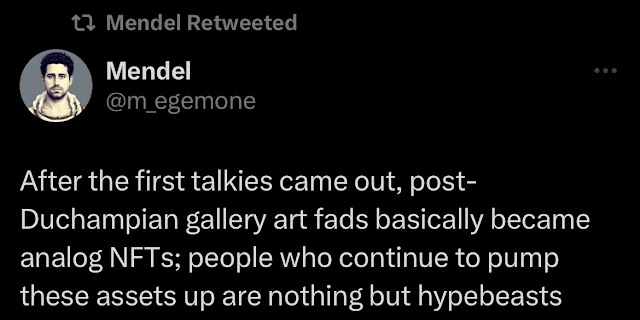

I also added something because the asshole made a comment about Ganz' connection with Zwirner. Ganz is now writing for Artforum and has a piece on Richter.

I don't know what this guys fucking problem with me is but this absurd. I don't have any "proximity" to David Zwirner, you can not like my writing but implying that I wrote it on behest of the gallerist or whatever is scurrilous https://t.co/BeAXHnhnDp

— John Ganz (@lionel_trolling) May 6, 2023

Fine art is a luxury commodity. Galleries are luxury boutiques, not bookstores. And of course you're connected to Zwirner. When you were an "artist" in Bushwick did you have any friends who were born there? Any social connection at all to the working class other than as idea? In 1993 Zwirner told me with a shrug to me that there was no difference between art and fashion anymore. Art is now style, and HBO has more art than Chelsea. Panofsky was right. Fine art and couture are vestiges of the old regime. Art for the rich. The connection to philosophy is tied to that and the lie that philosophy is superior to fiction, as theology concerns "truth" and fiction is lies.

All of the above is obvious in 2023, except to pretentious American liberals who call themselves leftists: Ganz and the Brooklyn Institute. I have friends born in Bushwick and I've known Zwirner for 30 years. Ganz the earnest gentrifier doesn't talk socially to art dealers, art collectors, or the working class. The only union members he knows are grad students, or maybe WGA, probably not even even IATSE. He stays in his bubble, and that's never good. Now I'm wondering if the Richter show I mentioned is the one where I told Roberta Smith that she had her head up her ass writing about late Picasso. Saltz was there too. About Richter he asked me "Do you really think this is art for the ages?" I said, of course not, but I was sympathetic. I should have asked him if he thought Donald Judd was art for the ages, but that would have started a whole new fight, with his wife.

...and this development is all the more interesting as it took place under conditions contrary to precedent. It was not an artistic urge that gave rise to the discovery and gradual perfection of a new technique; it was a technical invention that gave rise to the discovery and gradual perfection of a new art.

But Panofsky is wrong. If we want to be optimistic, the relation of art and and technology is reciprocal. Pessimism—or materialism—says art follows technology: secularization and the printing press, painting on walls or wood panels that can be bought and sold, theater and the novel, the rise of the middle classes, democracy. We're back to free will and determinism, which goes back to Richter and HBO and the Nolan brothers, Westworld, Devs, Tenet, The Dark Knight. But as a teacher of mine said about Gursky, "he used to be a nihilist, but he sold out". Another old story. The same is true for Richter.

But that's why the asshole was wrong. It's not that the "fine" art is meaningless, only which forms give us the most compelling description of the present.

I can't make a living at any of this—art or criticism—only because I'm always best at pissing people off. Talking to a woman at Christie's a few years ago I said only billionaires could be honest talking about what they liked and why, but that I was raised to behave as if I were a billionaire. She looked back at me and smiled sweetly. "Then you're free." I guess I am. The rich and the poor can be honest. Everyone else lies to themselves first, and then everyone else.

Ganz helped to gentrify a working class neighborhood, admitting he formed no social connections to people who lived there; he writes about romanticism, the sublime, and hope, as manifest in multi-million dollar baubles on display in a luxury boutique, and with earnest moral fervor about the killing of a homeless man on the subway, all without the slightest sense of self-awareness.

Richter's work at best is a notch above kitsch, describing a desperate need for cheap sentiment to be more than it is. Modernism is full of that, and I have a sympathy for it. He's fighting his own numbness. Ganz by comparison is earnest, shallow, callow, self-absorbed, self-serving, and on down the list. From my grandfather's job as a hired killer to my father's essay on Hammett, I have him cold. It doesn't matter.

I remember walking around the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, sitting in on crits, and one student's video, or it might have been a film, which was nothing but him on a beach yelling at the sea, shouting his name at the top of his lungs at the surf, demanding to be recognized: an over-the-top, absurd, derivative but full-throated performance, an expression of humility.

If a character in a novel lights a cigarette, the cigarette is part of a work of art. In a play the cigarette is a prop. In the older definition of art objects the craft supplied a formal logic internal to the piece. The iconography supplied a formal logic external to it. For relics as opposed to artworks the logic was external only: absent its place in a narrative a thighbone is a thighbone, a cigarette is just a cigarette, a madeleine... etc.

Duchamp has a tag. click it.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comment moderation is enabled.